How to design a referral program

Above: Dropbox’s innovative growth initiative — A referral program to give/get storage

Why a referral program?

Referral programs — the “give $5, get $5” offers you see in many apps — have become popular in recent years. They have big advantages over paid marketing channels, in that you give your CAC to your users, who then spend it within your product, as opposed to handing it over to Google or Facebook. Because they are a form of viral marketing — utilizing your network of users to bring in more users — they tap in to your product’s network effects, as I describe in The Cold Start Problem. This is particularly useful for products that target high acquisition cost niches, whether that’s crypto users or on-demand drivers, whose CAC are often >$200, since the users often know each other.

A successful referral program can be 20-30% of your acquisition mix, as one of several acquisition loops. It’s not a silver bullet, but it’s worth adding to complement other marketing efforts.

The history of the referral program

How did a structured form of customer referrals come into being? It’s said that the first documented referral program was created by Julius Caesar, who in 55 BC would paid his soldiers 300 sestertii (something like a third of their annual pay) to refer a friend to join the army. And thousands of years later, we still use, plus or minus, the same idea. It seems as though every consumer app has implemented some form of a referral program, though I argue it really kicked off in ~2008, which is when Dropbox’s innovative referral program was rolled out.

Yes, the most famous early implementation of referral programs came from Dropbox, which inspired a generation of startups — particularly YCombinator-backed startups — to experiment with similar ideas. Why did this make sense for them? CEO/cofounder Drew Houston’s made a very helpful presentation describing his journey towards referral programs, and the general trajectory was the following:

- First, do all the things you’re “supposed” to do

- Big bang launch at a tech conference. Try some AdWords, hire a PR firm / VP of Marketing

- Paid marketing programs created a CAC of $233-388 for a $99 product

- Then trying affiliate programs, display ads, and many other things — which all failed

- … but then failing! And realizing none of it works that well

- Then realizing the key was to accelerate word-of-mouth and viral growth by offering a “give and get storage space” program

- Boom. 100,000 users to 4 million in just 15 months, with 35% of daily signups

The entire deck is wonderful — created roughly a decade ago, but still very relevant — and I highly encourage you to check it out here.

Referral programs work very well for certain kinds of products, particularly ones that are already spreading via word of mouth. In Dropbox’s case, there is a natural use case between friends and colleagues — shared folders — which naturally complement the referral channel. Referrals drive that forward, providing an economic incentive to tell friends. As another example, at Uber where I ran the referral programs for drivers and riders at various points (and spent >$300M/year on them), the program for driver referrals was naturally successful. Drivers were often from certain sub-communities, whether newly arrived immigrants or limo drivers, and people were naturally already talking about the earning opportunity. Referrals, sometimes as high as $500/signup, accelerated that in a big way.

And yet referral programs have their limits. Of course they don’t really work that well for products that have low LTV — that’s why we don’t see free social photo sharing apps reward their users for referrals. There’s no LTV to arbitrage against, and the referral amounts create a form of customer acquisition cost. They also tend to decline in importance over time. Years after the rollout of Dropbox’s referral program, I had the opportunity to join Dropbox as an advisor, where I got a first-hand look at the data. By then, the natural virality of their core product — just the process of people sharing their folders and files with others — had come to completely dominate user acquisition. This had become the primary method of spread, and the referral program became much less important. I’ll discuss why, later on, but this seems to be the natural pattern of things — referral programs are very helpful at the beginning of a market. Eventually it becomes less important, and that’s OK.

But we get ahead of ourselves. Let’s start first by looking at how a referral program is usually defined.

The structure of a referral program

We see the same rough patterns in referral programs that are implemented across the industry. Airbnb, Uber, Instacart have them, and so do Coinbase and Wealthfront. There are variations of course, as some focus on giving and getting dollars. Some ask you to share a code, or a link, or connect your addressbook to invite friends.

One way to organize all these variations is to divide them into the following — and you need to answer a series of questions for how you structure the program:

- Ask

- When do you ask the user to refer?

- Why do you refer? Is it tied to a holiday, or a particular promotion?

- What’s the message?

- Target

- Which users do you target? All of them?

- How do you set referral amounts?

- Incentive

- What’s the incentive, is it extrinsic ($) or intrinsic (points, storage, etc)?

- Do you give the inviter or recipient the same reward?

- Payback

- What is the success criteria for the program?

- How do you think about cannibalization?

Let’s use an example to describe this.

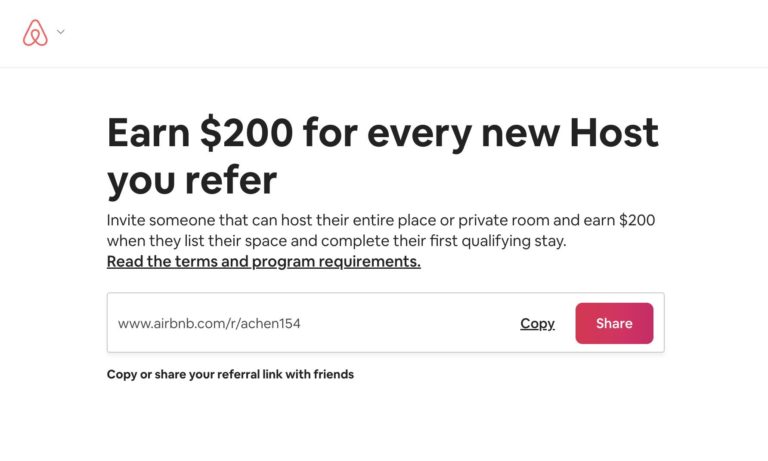

For example, take Airbnb’s host referral program:

You could break this down into the following categories:

- Ask: Invite someone who can host their entire place or private room

- Target: All Airbnb users

- Incentive: Earn $200

- Payback: CAC is better/comparable to other marketing channels (just speculating!)

This is the basic structure, and now that we have this in place, it’s time to talk about a number of design considerations needed when creating a referral program.

The Ask

Product folks often start by agonizing over the ask. They wonder if it’s too trivial to create a “Get $5, Give $5” referral program, or if that’s too basic. But I think that’s the wrong place to focus — after all, you can always word smith and test many variations later once you have the program up and running.

The real question is, WHERE do you make the ask? And my answer is simple: Ask many times, in many places, with different messages, and in-context with whatever action you’re asking the user to take. What you find, after instrumenting all your referral UI, is that there’s just a certain conversion rate on this screen. And that most users, if you put the referral functionality on a banner somewhere random in the product, simply don’t interact with the referral features. Rather than trying to raise conversions, instead, show the screen more often — get more impressions!

Thus, make the referral ask part of the main flows. After the user is buying something within your app, ask them if they want $X cash back now, by inviting someone. Or if they interact with a friend within the app — assuming the product allows invitations of some sort — follow up by asking if they want to invite others. And add it to the onboarding flow, and at the end of key transactions when the user is otherwise done, and you might as well capture engagement. And for god’s sake, don’t make it look like “an ad” with big splash text and graphics — make it plan, like something that’s part of the normal UI where the user can interact.

One of my favorite ideas from Uber is the concept of “holidizing” a referral campaign. For drivers, as the holidays approached, you might tell them to earn extra money towards gifts and festivities, by participating in a referral program. Or for the run up to a major concert in town, you might run a special tiered campaign where referring 1 friend gets you X, but 5 gets you 5*X and a huge bonus on top. There’s something great about freshening up the messaging each month to align to major holidays, with new amounts, new imagery, and otherwise.

The Target

The headline best practice is that your referral program should target new users to refer their friends — this means prompting users during their initial onboarding flows, and adding emails as part of the onboarding, among other surface areas. This is in direct contradiction to folks who often argue to let users experience the product first, have a good experience, before they’re hit up to invite. Why focus on new users? First, mathematically, it’s easiest to make a big impact when you are hitting a cohort of 1000 new users when it’s as close to 1000 as possible, not in day 30 when the cohort will have churned and gotten down to 150. And in the math of the viral factor, you have a better chance to hit >1 when you have 1000 users invite 1000 users than to ask 150 to invite 1000. Second, new users generally have more friends who haven’t yet used the product, because they are new themselves. Once they have gone through the referral program a few times, then they will have naturally tapped out their networks.

And of course, the simplest thing to do is a “give $5, get $5” and give that offer to everyone, in an untargeted fashion. But a product leader soon realizes that this is inefficient — perhaps it’s best to give some users $15 and others $5, depending on their value. This is exactly what many marketplace companies have done, when it’s easy to segment their network into high-value cities like New York and SF versus, say, Memphis — you can set custom referral amounts in each place. But why stop at cities? Perhaps you do an analysis and figure out certain leading characteristics of high-value users as their account balance, or the types of other apps they use, or otherwise — once you think of this as personalizing an ephemeral offer to users, then you can run whatever promotions you want.

The Incentive

You’ll note in the original Dropbox offer, the incentive itself was storage space not dollars — this is the dilemma of intrinsic versus extrinsic rewards for users that participate in your program. Many referral programs for mobile games tend towards intrinsic rewards as well, earning you points if you invite friends. The advantage of intrinsic rewards is that it’s particularly cost effective when the incentive is something you can control, like points. The problem with intrinsic rewards, of course, is that external users — people who have never heard of your product — are the least responsive to points or otherwise. Dropbox’s storage offer is maybe somewhere in the middle, since it’s at least a concrete form of value. As a result, most referral programs have tended towards dollars over time, though I think the important idea is to prioritize new, outside users, and think about how to make the incentive as concrete as possible.

There’s the basic question of how to set the incentive amount. Typically this is based on a basic calculation of CAC/LTV, which has major weaknesses as it doesn’t take into account cannibalization (which we’ll discuss later). Instead, the focus is often to pick a simple number — if you know that the average user who signs up spends $20, then you can create a referral program that rewards a $5 give/get with some margin of safety. But the big lever on the incentive, of course, is to increase the amount — and the largest amount generally comes from tiered offers that have some form of breakage. An example of this is to say, “$100 when you sign up and buy 5 things” rather than “$5 when you sign up.” Given that the difference between a signup and a repeat conversion rate might be 100x, you might be able to safely raise the amount 20x. At Uber, this went so far as to combine two distinct numbers: A headline number that combined both the initial signup conversion as well as the first month’s earnings (again, as long as you drove X trips in the first few weeks). This resulted in a $3000+ number, a huge upgrade from the initial $200 numbers we started with. These larger headline numbers always tested much better on A/B tests, whether in email marketing or banner form, and while it might feel like the reward becomes unattainable, it’s possible to create a second or third or fourth tier to go along with the big headline number. You could say, earn $X when you fulfill all the requirements, but then a smaller number, $Y, when you only fulfill a few. That way you get the marketing impact of the big number but still have a fallback for users who don’t hit all the milestones.

The last aspect of the incentive structure I’ll discuss is a symmetric versus asymmetric offer — that is, should it be a “give $20, get $5” or “give $5, get $20.” Which one sounds better to you? This is anecdotal, but in testing I’ve seen, the inviter-centric amount generally works better — that is, catering to their self interest. However, I’ve also seen B2B contexts where in a professional setting, people tend towards inviting more if they are perceived as altruistic, giving out a large $ discount to others. In the end, probably just worth A/B testing to see what works best.

The Payback

You’ll need some kind of ROI metric to drive the strategy of the referral program. Are you spending the right amounts, or should you increase the numbers? How much product effort should be put into implementing new surface areas? Etc. Is it working? These fundamental questions are often answered with a classic CAC/LTV analysis, and there’s a reason to doing that.

After all, if the lifetime value of these users exceeds the cost of acquiring them, shouldn’t you just go full steam ahead? Well, maybe. What if you can get much cheaper acquisition via another channel, like TikTok ads. Then any dollars that go to this might be better spent on ads. Or what if improving a referral program takes engineering team away from critical features? So yes, of course look at the CAC/LTV of your referral initiative, but think about how you might compare the tradeoffs against everything else.

The trickier ROI question is cannibalization: How many of the users that you bring in via referrals would have come in through word of mouth anyway? If you spike the referral amounts, going from $5 to $20, are you just creating a “pull forward” effect where users that would have arrived for free a few months from now are coming in suddenly, but at a cost, and to the detriment of a later month?

Cannibalization is a hard effect to tease out, but generally the goal is to measure something like “Cost Per Incremental Customer” by A/B testing offers to a control group that gets the standard number, and a test group that gets the elevated number. Because you’re trying to capture organic users, you often have to do this as a “twin cities” experiment, where we run one set of offers in Phoenix and another in Dallas — this is the Uber approach, and in B2B you might do it via one set of companies versus another. And then you measure what the uptick actually looks like. If there is a lot of cannibalization, then the CPIC number will be large — this is the true CAC, cannibalization aside.

The other, simpler form, is simply to do an “On/Off test.” If you turn off all your referrals for a few days, do you notice a big drop in new users? If yes, then your referral program is working. If not, then you are potentially paying a lot of customer acquisition cost for something that would be happening anyway.

The weaknesses of a referral program

As I mentioned at the intro of this essay, Dropbox’s eventually became less dependent on their referral program. There’s a natural trajectory here, because as the market matures and more users have already adopted the product, the fewer friends there are to invite. You only need a few “I already have that” responses to stop participating in referrals altogether. For products that have a true network effect, as Dropbox does, the acquisition will eventually be taken over by intrinsic use cases like folder sharing rather than something as extrinsic as a referral reward.

And in a way, I find myself mostly skeptical when teams approach me to build a referral program. The first thing I ask is, are you sure you wouldn’t rather build a viral growth engine? Building viral features and a referral program are similar problems — trying to get users to invite friends — but truly viral features around sharing and communicating are evergreen and create lasting value. They help users engage and retain, and as a secondary effect, generate new users as well. And it’s a huge benefit to get these new users onto your platform for free. For Dropbox, that means investing in product features like inviting teammates into projects, or file sharing, or otherwise, rather than creating ever more complex referral structures. At Uber, this might mean building virality into features like “Share ETA” or bill splitting or group food ordering.

In that way, I find myself a reluctant fan of referral programs — they can work, and can become a 10%+ acquisition channel for products — but they will always take a back seat for me, compared to building great viral functionality.

texto por Andrew Chen