Principais insights da Aula #03

com Tiago Reis sobre Viralização

- Autor do post Por Michell Lucino

- Data de publicação setembro 22, 2022

Principais insights da Aula #03

com Tiago Reis sobre Viralização.

Viralização. Primeiro, falar o que não é viralização (ou não deve ser). Luva de Pedreiro viralizou; Bora Bill viralizou. Tem muita coisa aleatória e não dá pra padronizar – só se descobre se vai viralizar depois que já viralizou, não dá pra prever tudo na vida. Mas viralização não é só “o próximo Luva de Pedreiro” ou o próximo “Bora Bill”. Às vezes, é melhor ter várias coisas pequenas dentro de um público em específico, que é o caso da Suno.

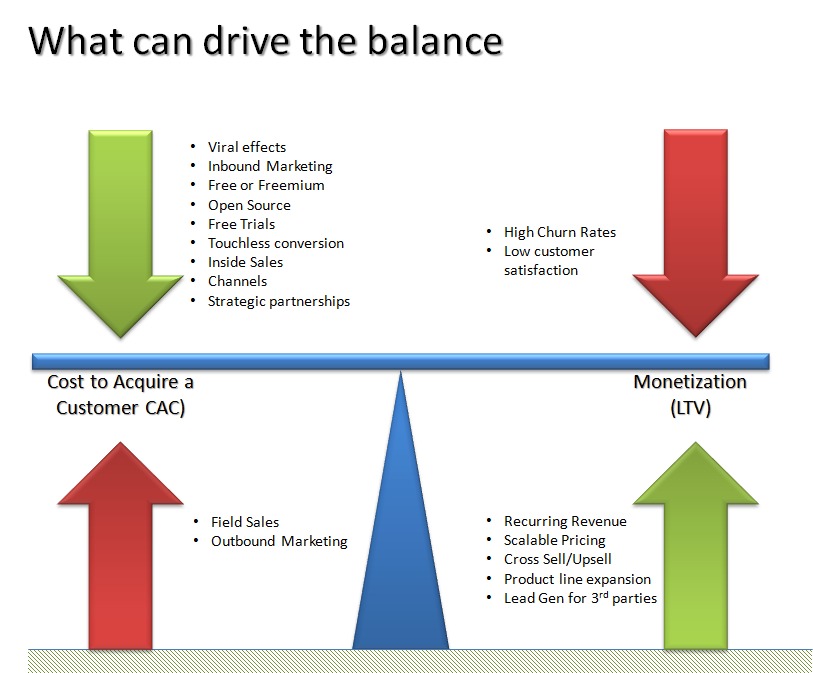

Viralização pode ser coisa pequena também. É sobre ter os outros falando de você (e, com isso, ter um custo de aquisição menor). A melhor forma de viralizar é ter uma boa experiência de usuário – nada supera isso. Se tiver uma experiência foda na Link, você vai recomendar com certeza.

Conteúdos que viralizam:

– Newsjacking (se infiltrar nas notícias dos outros no início de quando e colocar seu ponto de vista em cima) e nem toda viralização é boa, porque o apoio vem de um lado e as críticas vêm do outro. Algumas marcas estão se posicionando desse jeito e colhendo bons frutos e aumentando custo de aquisição. Havan com Luciano Hang: gastos de publicidade com relação à receita estavam caindo e a receita estava aumentando bastante. Existem também os truques de headline (exemplo: Petrobras acaba de cometer a maior fraude da história; entenda). O desafio é ter processos pra fazer isso acontecer quando precisa acontecer, no timing certo;

– Public Relations é usar veículos de imprensa (que envolvem desde jornais até influenciadores) ao seu favor. Amizade e networking importam nesse momento e ser a “fonte do conteúdo” também ajuda. A Suno começou em uma parceria com o InfoMoney – os veículos de comunicação precisam de conteúdo e os jornalistas precisam de dinheiro: se você facilitar a vida do cara, pode dar jogo;

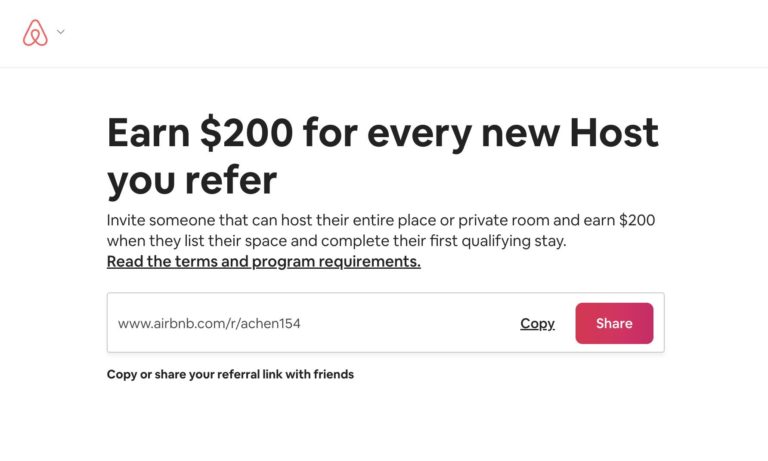

– User Generated Content é fazer com que os usuários falem sobre seu produto e sobre você. O que funciona para UGC é pedir explicitamente para o cliente e também oferecer incentivos.

– Make your customer successful. Exemplos do Spotify, Headspace, Peloton, Nike Run, Apple Watch etc., nos quais a entrega do produto faz o cliente se sentir melhor com números e, consequentemente, postar sobre isso.

– Create a community. Link tem isso naturalmente e é algo muito difícil de ser feito, mas quando pega, pega forte.

A ideia aqui é encarar isso como uma série de ingredientes e daqui pra frente se inicia a arte de misturar as coisas.

A oferta de conteúdo é cada vez maior para a mesma atenção. Para aumentar o share de atenção, então, provavelmente vamos precisar fazer os outros falarem de nós.

Como a Suno usa: redes sociais, 100%. Tem que acompanhar – quem não mede, não gerencia. Tem que planilhar tudo: Instagram, postou tal conteúdo, tal horário, tal link, tal objetivo e depois KPIs de engajamento. O processo deles é: 100 conteúdos por dia (em todas as redes do Tiago) e qualidade está no olho de quem vê (precisa conhecer muito bem sua persona) e qualidade não é só o conteúdo e a mensagem, mas também a forma como você se expressa, a imagem, takes diferentes, de um jeito inovador e engraçado etc. (transformar sua empresa em uma empresa de cinema) – as pessoas gravam muito mais a forma do que o conteúdo. Exemplo do Gary Vee de como traduzir um conteúdo grande para infinitos conteúdos menores distribuídos ao longo do tempo.

Estratégia do “5º P do Marketing além dos outros 4” como propósito/posicionamento e usando o exemplo da Havan e do posicionamento do Luciano Hang.

4 passos para uma viralização inevitável: 100 por dia, todos os dias, qualidade e sempre com CTA. Estudar um pouco mais sobre Conversion Rate Optimization e entender dá pra aproveitar para, por exemplo, o Tik Tok.

Nada supera a experiência do usuário. Magicamente, se você foca nisso, o resultado vem (mas costuma tomar tempo).